The Weekly: Takeaways from 2025’s Climate Disasters

Twenty-three billion-dollar disasters, $115 billion in damage, and not one hurricane: 2025 was a masterclass in how climate risk in the U.S. has changed.

Municipal leaders have an opportunity to lead their communities to a resilient future and mitigate flood risk. A case study from Algonquin, IL highlights resiliency investments that have fundamentally transformed how flooding affects the community and have yielded significant cost savings.

By Erin Delawalla, The Epicenter Contributing Author

Municipal leaders have an opportunity to lead their communities to a resilient future and mitigate flood risk

When flooding disasters occur, local governments are expected to manage the crisis in the near-term and reduce losses in the long-term. They are expected to identify flood risks, address those risks, and do so without burdening residents with significant costs.

No one knows this better than local officials whose communities have experienced a catastrophic weather disaster like a flood. Amidst the disaster, officials take calls in the middle of the night from panicked homeowners worried that their basements are filling up with storm water or that the nearby creek is overflowing into their backyards. These officials host numerous public meetings to address residents’ concerns about what can be done to prevent future catastrophic flooding. And officials spend hundreds of hours managing the reconstruction of community infrastructure as well as helping homeowners navigate claims that have been sent to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) for things like black mold or basement damage.

But local leaders don’t always realize the power they have to do more than just react to disasters; they can and should also play a role in preventively preparing their communities for future weather events. That’s because local government officials are best positioned to know where the pain points are and can best take ownership of rebuilding and planning for future crises through planning and investment.

Michele Zimmerman, Assistant Public Works Director for Algonquin, IL–a suburb of Chicago– has experienced many of these situations in her 30 years working for the village. According to Zimmerman, 20 years ago, everything would flood during a typical "1 to 2 inch" rainfall event. Roads were closed, backyards were flooded, and culverts were clogged. People had standing water in their yards because detention basins didn’t function well. In a typical storm event, the village staff would be all-hands-on-deck to clean storm sewers and backyards, move debris jams out of creeks, and direct traffic away from flooded roads.

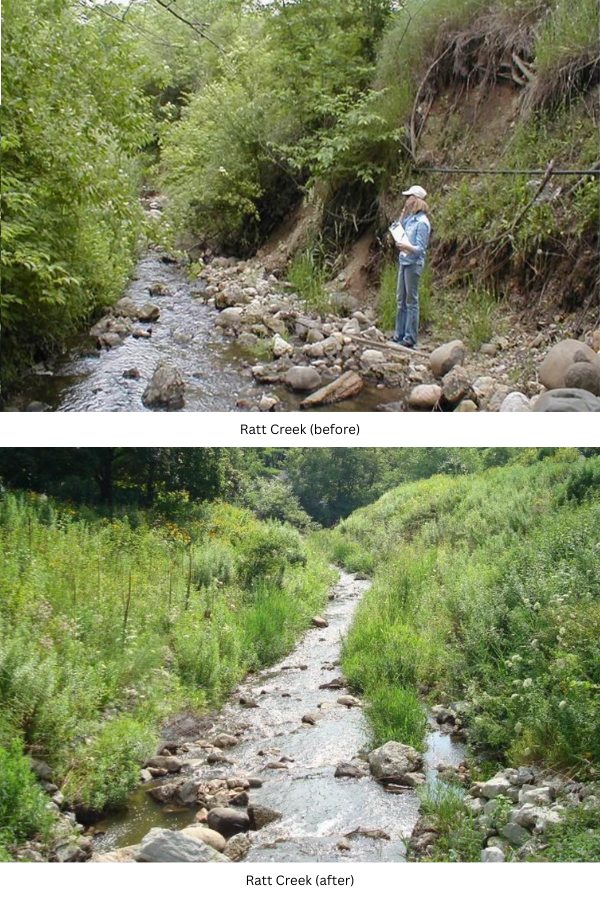

Zimmerman saw an opportunity to change how Algonquin managed water: from reactive crisis management to proactive capacity building. In recent years, Algonquin has made intentional resiliency investments that have fundamentally transformed how flooding affects its community. Algonquin is one of the rare communities that have invested in resiliency proactively by systematically identifying opportunities to incorporate resilience into their environment to alleviate flooding, enhance public resources, and even save money for Algonquin on maintenance costs.

Back in 2005, Algonquin’s population was growing, as was the amount of impervious land use (i.e., hardscape like cement, asphalt, houses, shopping strips, etc.) that prevents excess water from infiltrating into the ground. Older developments were not designed with stormwater in mind, and the net effect was more flooding. The default solution in the U.S. at the time was to utilize gray infrastructure–conventional hard materials, typically made of pipes, concrete, steel, and artificial detention basins–to control and store water to address flooding. The approach to managing stormwater was also handled at the individual parcel level, rather than taking a watershed view. This can result in development eliminating more water storage than it replaces, which can exacerbate flooding.

Zimmerman had learned of a different approach to water management, one that uses ecological principles to mimic nature to hold and infiltrate water. This approach is sometimes referred to as “green infrastructure” or “nature-based solutions” (NBS). Algonquin lent itself well to these strategies, as it has many wetlands and streams flowing into the Fox River, which flows through the middle of town. County-level requirements were starting to require detention for new developments and encouraged naturalized versions of these solutions (e.g., using native grass in a detention basin to mimic a wetland rather than a turf grass bottom). Water infiltrates faster into the ground when native grass is planted versus turf grass.

Solving flooding is never an easy fix, but developing a watershed plan to identify the problems and opportunities can turn a big problem into manageable steps. For Algonquin, there was not a single large project that solved all flooding issues, but rather a programmatic approach that changed how water was managed throughout the whole community over time. In 2005, the Algonquin Public Works Department began by completing a natural area inventory plan, which identified the challenges and the opportunities within Algonquin’s watershed. The plan created a roadmap for the community to incorporate resilience one project at a time. In 2013, the Village drafted two 319 Watershed Plans to further streamline and direct these resiliency efforts.

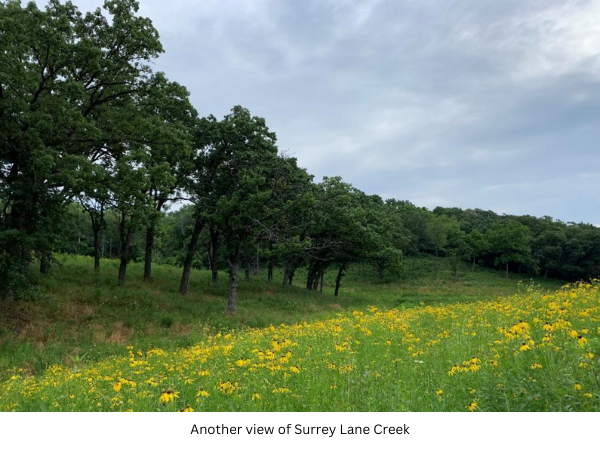

Public education on the benefits of this new approach was another key step for success. Zimmerman and her colleagues in the Public Works Department spent time educating the village’s board about the benefits of these approaches over gray alternatives. Her team explained that green solutions would not only last longer, but also were cheaper than the gray strategies. While the board embraced the strategy quickly, it took residents longer to be sold on the plan. Locals who lived next to creeks and detention basins initially pushed back. They were resistant to change and did not initially like the aesthetic of native vegetation, which they thought looked like weeds. Within 3 to 5 years after a project was implemented, with flooding reduced, residents have started calling the village’s Public Works Department asking for more projects to be done in their neighborhood. In particular, they have noted their appreciation for the wildflowers and aesthetic improvements that the projects have brought to their community.

Although Algonquin has received more rainfall than it had twenty years ago, flooding conditions there have dramatically improved. The Illinois State Water Survey Bulletin 75 indicates that over the past century, Illinois’ average annual precipitation increased by 11% (from 36 to 40 inches) and the number of storms producing over 2 inches of rain has nearly doubled. It’s not just Algonquin getting more rain. The majority (85% or 2,645) of 3,111 counties in the U.S. are likely to experience a 10% or higher increase in precipitation as temperatures warm, according to a Climate Matters analysis based on National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) data.

Algonquin is ready for wetter conditions thanks to key strategies they are implementing:

Both watershed plans are being updated, as they are both 10 years old. In the Jelkes Creek-Fox River watershed, the village has completed over half the projects in that plan. In the Woods Creek watershed plan, the village has completed over one-third of the projects. Zimmerman says she wants to implement every single project

Even without completing every identified project, Algonquin is already seeing the benefits of its investment. Zimmerman tracks the maintenance costs for the village to demonstrate how this approach is saving the village money.

The village’s traditional landscape contract covers approximately 220 acres, which includes landscape beds and turf grass that has to be mowed. The contract costs $431,000 per year.

In contrast, the Village’s contract to manage natural areas costs only $150,000 annually, despite encompassing a much larger area: approximately 470 acres. Instead of mowing and non-native annual planting, the Village uses prescribed burns, targeted herbicide, and time for native vegetation to establish. And, as seen below, the natural areas look equally as stunning as any landscape bed.

How can local governments take similar steps toward resilience?

Local governments will always play a significant role in responding to disasters like floods, but they should also be involved in helping to build resilient communities before the disasters hit. They have the unique expertise required to identify where funds are needed and determine how to fix problems, and can work with other community leaders and residents to ward against future weather threats.

This article is the first in a series about the role that different levels of government can play in addressing flooding.

Erin Delawalla led nature-based solution development for community resilience needs in the Midwest for RES, the nation’s largest operational ecological restoration company. She worked to develop innovative funding strategies for environmental restoration. Delawalla is a licensed attorney with extensive experience in permitting issues related to renewable energy and natural resources. She previously worked at a large renewable energy developer, managing wildlife and wetland issues for over a gigawatt of utility-scale wind and solar projects.

Have thoughts to share on this piece, or want to add your voice to the conversation? Reach out!