The Weekly: Takeaways from 2025’s Climate Disasters

Twenty-three billion-dollar disasters, $115 billion in damage, and not one hurricane: 2025 was a masterclass in how climate risk in the U.S. has changed.

In a world of more frequent climate stressors and disasters, parametric insurance is a fast, nimble way to compensate communities for losses. Its growing popularity in the disaster space (from earthquakes to hurricanes) makes it a necessary tool to help communities bounce back.

No where is the proverb “Necessity is the mother of invention" more true than in today’s insurance industry.

The frequency and severity of disasters are forcing insurers to rethink everything: from premiums to the products themselves. Insurers are racing to update their models, reduce exposure, and develop products for risks that were once too diffuse or difficult to underwrite.

The industry has no choice but to innovate. That’s the contention of Roy Wright, the CEO of the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS).

The need might appear most acute in home insurance, where state markets, like California's, are “not functioning.” But new insurance products are needed to address a range of hazards, and the deadliest hazard in the United States is not wildfires, but extreme heat.

In this article, we explore the frontier of insurance innovation by examining an emerging insurance product: parametric heat insurance.

Extreme heat is the deadliest type of disaster in the United States, killing over 2,000 people in the U.S. in 2023 alone.

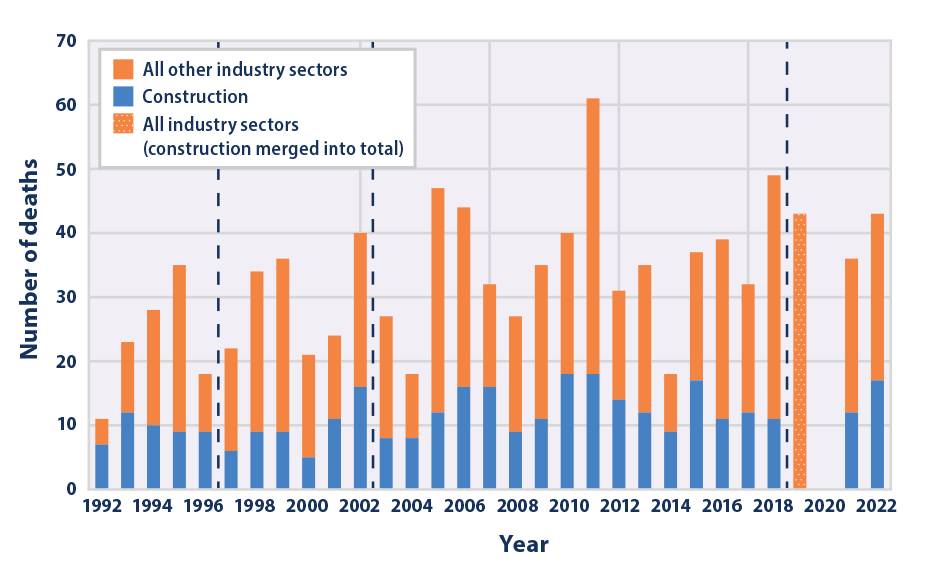

In the 30-year span from 1992 to 2022, the average number of official heat-related deaths occurring on the job has hovered around 30-40 per year in the U.S. But these estimates could be off by a factor of two. A Tampa Bay Times investigation found that in the last decade, across just the state of Florida, twice as many workers (a total of 37) have died from heat than official records indicate.

Research from the U.S. Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) found that:

There are several ways to protect outdoor workers from extreme heat. OSHA has detailed prevention recommendations for new workers, including limiting work duration for new workers, building their heat tolerance, and providing ample shade, fluids, and rest.

But new parametric insurance policies offer an alternative: paying outdoor workers not to go to work on hot days in the first place.

Here’s how it works: A parametric heat insurance policy automatically pays out when a predefined extreme heat threshold is reached. Parametric insurance policies for extreme heat are designed to provide quick cash relief, allowing outdoor workers to stay at home or take breaks on days when it may be unsafe to be outside.

Unlike traditional insurance policies that indemnify against actual losses incurred, parametric insurance policies use an “if/then” trigger related to the event occurring. For example, “if the local temperature exceeds 100°F for 3 days, then pay $500 to the insured within days of the event happening.”

Swiss Re has been ahead of the curve in identifying heat as a growing dimension of climate risk and doing the pioneering work to build new insurance products to minimize that risk. Earlier this summer, it released a report on the insurance fallouts of extreme heat.

Jackie Higgins, Head of Swiss Re’s Public Sector Solutions US practice, has begun to see a growing interest from municipalities in parametric insurance products of all kinds. Many public sector actors are still in the early stages of learning about these products. “They are starting to see parametric insurance as a potential form of quick budget support in the event of a major event,” she said.

For parametric heat insurance specifically, Higgins has been in initial conversations with U.S. state-level municipal leaders about how to design a program and determine what triggers a payout: the temperature on your phone, temperature and humidity, or the wet bulb temperature. “When designing a new insurance product, simplicity is best,” she said. “Everyone needs to easily understand how it would work.”

Parametric heat insurance isn’t common in the United States yet, but there are a number of case studies and pilots internationally:

Many parametric heat insurance policies remain in their infancy, characterized by small pilots with small payouts.

Could they scale? Globally, the need is there. More than 60% of the world’s workforce, or approximately 2 billion people, makes a living in the informal labor economy.

Parametric insurance policies of all kinds are growing. Swiss Re, reported that sales of parametric products increased by 40% between 2021 and August 2022. The parametric insurance market is expected to triple by 2031.

However, there are limitations to parametric climate-triggered insurance policies, like heat policies.

First, there’s the question of long-term financial viability. If the products are not structured properly to capture the most severe events, then payouts could happen too often due to more frequent periods of extreme heat. This could cause premiums to rise, making it unaffordable to purchase, and insurers might determine that the product doesn’t make financial sense. In Kenya, the Kenya Livestock Insurance Programme (KLIP), a parametric insurance program aimed at addressing drought, was ultimately not financially viable. It ended after seven years of operating at a loss.

Second, parametric heat insurance policies need the right mix of partners. For the initial pilots, nonprofits or governments often cover the premiums. But for parametric heat insurance to reach a greater scale, the insured themselves would have to determine that it’s worth paying the premiums.

In the United States, the insurance markets vary state by state. A parametric heat insurance program in California would need to be tailored before it could work in Arizona or Florida. Even then, it can take time to get the buy-in from the necessary public sector stakeholders and state-level insurance regulators to launch a pilot and understand the mechanics. Higgins from Swiss Re said this can take years to align stakeholders and ensure the financial structuring is compatible with state regulations.

Such challenges could indicate that the applicability of parametric heat insurance is limited in the United States. That is, until people begin to feel the heat.

In a world of more frequent climate stressors and disasters, parametric insurance is a fast, nimble way to compensate communities for losses. Its growing popularity in the disaster space (from earthquakes to hurricanes) makes it a necessary tool to help communities bounce back.

While parametric heat insurance remains in its infancy, the pilots so far might spur further innovations from other groups. Groups like Blue Marble are designing, launching, and scaling innovative new insurance solutions that bridge “the protection gap.”

“Insurance innovation in the United States will take a village,” Higgins said. “Our highly regulated environment means it can be a long, complicated process to bring new insurance products to market. But it’s not insurmountable. We just need people to lead the way."

Have thoughts to share on this piece, or want to add your voice to the conversation? Reach out!