The Weekly: Unaffordable Housing—A Hidden Driver of Wildfire Risk?

The housing affordability crisis and the wildfire crisis aren't distinct challenges. They're a self-reinforcing cycle that requires investing in resilience to break.

When disaster strikes, the question is not whether we will rebuild, but how. The problem is that it costs more to rebuild a home to disaster-resilient standards. We need new flexible and dedicated financing products that make it easier for homeowners to make critical resilience investments.

By Abby Ross, Contributing Author for The Epicenter and CEO / Founder of The Resiliency Company

In the wake of the latest disaster, people repeat the words their fellow Americans have said for years, “We will rebuild.”

This resolve and resiliency are embedded deep within the American psyche. It’s fundamental to who we are: we are a society that rebuilds, rebuilds, and then rebuilds again.

Today, the question is not whether we will rebuild, but how. And that question is becoming increasingly important because major fires, floods, hurricanes, and extreme storms are no longer rare, once-in-a-century events. Disasters are happening more frequently, with more severity, and in more places across the United States.

But the inevitability of the next climate disaster doesn’t necessarily have to mean the inevitability of destruction. In fact, new ways of designing, financing, and building homes in the United States offer a roadmap for those willing to think and build differently.

Today, it’s possible to build homes to new standards that increase the chances a home will withstand the next fire or storm, remain insurable, and even increase in value. I believe we’re at the dawn of a new era where resiliency is at the center of home building.

The challenge is that it costs more to rebuild a home to disaster-resilient standards. A 2025 report from Headwaters Economics found that rebuilding a 2,000 square-foot home in California to meet the state’s wildfire-resistant standards adds $30,000 to construction costs—up to a 10% premium on typical construction costs. However, when most insurance payouts fall below the baseline replacement costs of construction, many homeowners are left to cover these improvements out of pocket.

This is the "Resiliency Delta" – the financial difference between what current financing options cover and what it takes to build up to the highest safety and damage prevention standard possible.

Building homes to more stringent standards also requires extra effort and time, so it hasn’t been the default approach to building homes.

According to Kyra Peyton, Senior Innovation Manager at CSAA Insurance Group, people looking to take those extra steps face several hurdles—including a lack of awareness, additional time and delays, and extra upfront costs. Of the many obstacles, Peyton believes there are three that are critical to address.

I’ve heard it firsthand myself. Whenever I talk about the opportunity to rebuild differently after a disaster, I get the same question: “Who is going to pay for it?”

Financing is the biggest barrier to building to resilient standards outlined by the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS). If people don’t understand how such resilient standards are funded, nothing else matters.

The stakes are high. Home insurance is foundational to the U.S. economy because it transfers and distributes risk, allowing individuals (and businesses) to protect themselves financially from large losses. The pooling of risk enables property ownership, lending, investment, and development.

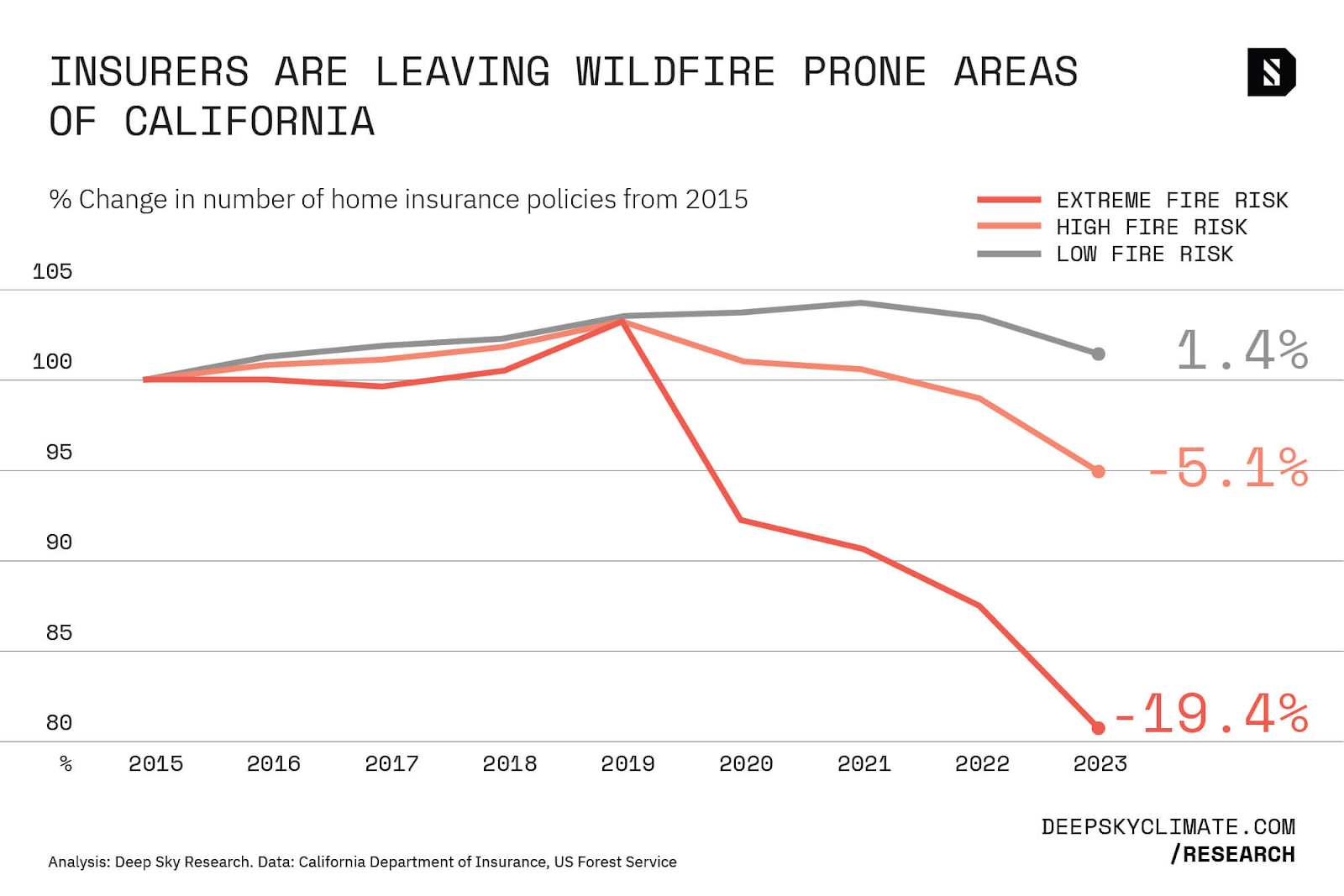

Homes in areas prone to repeat disasters could lose their insurance entirely—a phenomenon currently occurring in California, as insurers decide to cancel policies and leave the state.

If homeowners can’t get insurance, they can’t get mortgages. Without mortgages, property values drop. Dropping property values could lead to the hollowing out of cities as people move away and municipalities lose revenue.

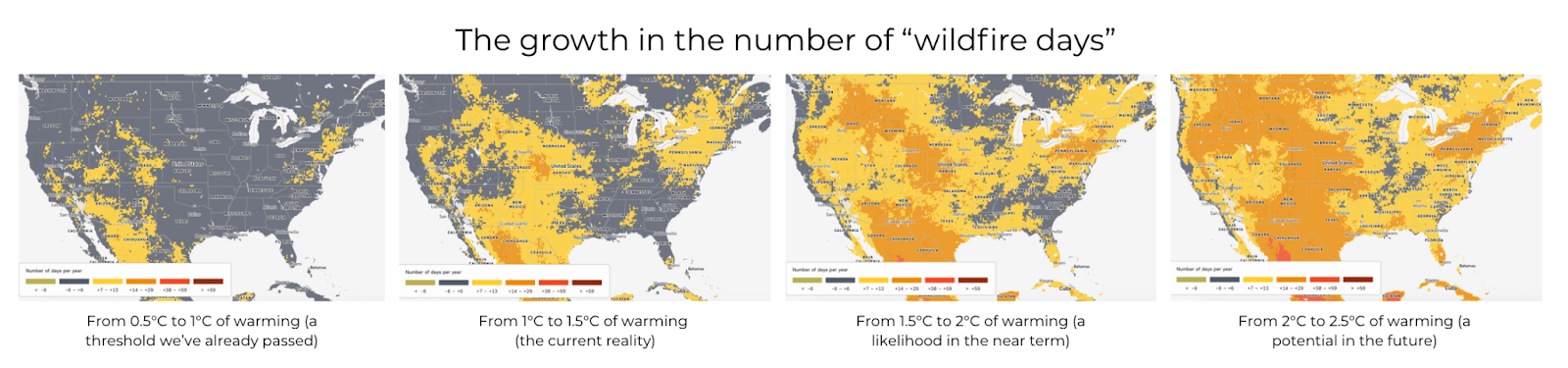

As the globe warms, the risks grow. Consider the following graphs from Probable Futures that track the growth in the number of wildfire days, measured as days when conditions exceed the top 5th percentile for wildfire danger, based on the Fire Weather Index at 0.5°C of warming (1971-2000) in a given location. As temperatures climb, the number of “wildfire days” extends to nearly every region of the United States.

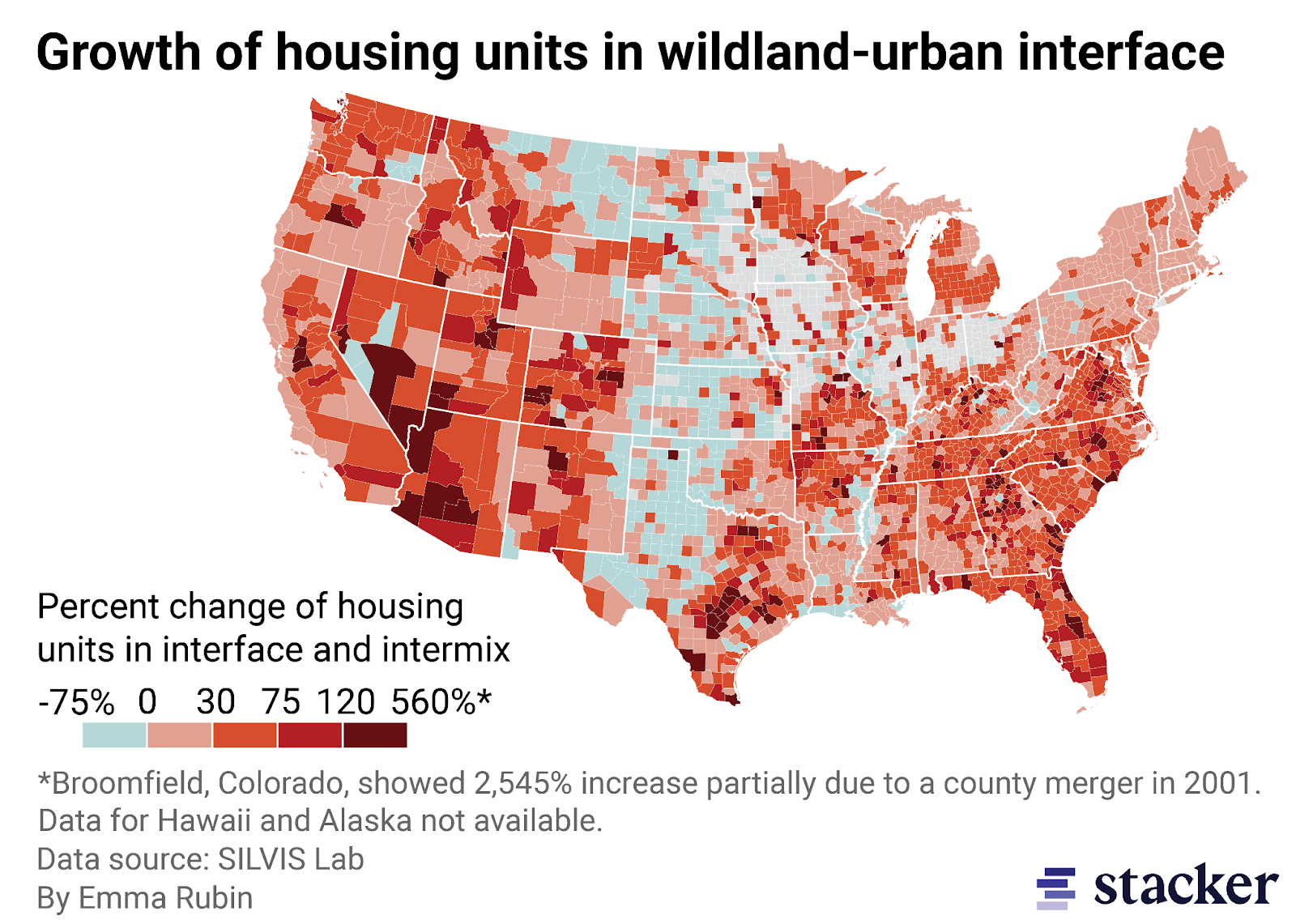

We’re also building in the most at-risk areas, like the Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI). The WUI is the fastest-growing land use type across the contiguous United States (today, one in three Americans lives in the WUI). The WUI covers only 9% of land in the U.S., but is now home to 39% of all houses in the country.

According to a report by Deep Sky Climate, the population in Extreme Fire Risk areas of California has not only grown since 2015, but it has grown faster than in lower fire-risk areas.

Today, one in five homes in the most extreme fire-risk areas have lost insurance coverage since 2019. Across the country, six million homes—7.4% of all homeowners—don’t have home insurance, amounting to $1.6 trillion of unprotected value. For individual homeowners without a safety net of home insurance, the next fire could mean personal financial ruin.

Not all insurers are retreating. In California, Mercury Insurance is writing new insurance policies for new-build homes and not canceling existing policies in places previously devastated by wildfires, like Paradise, California. It believes that the changes underway in building codes, fire mitigation, and community planning have reduced the risk of damage from wildfires. This nuanced approach is leading to underwriting more policies.

Homes built to fortified standards not only have a better chance of surviving the next fire, they have a better chance of getting and staying insured. The result: increasing the availability and affordability of insurance.

After a disaster, the window of time when a community is embarking on a rebuilding process offers a rare opportunity to align interests and incentives. In the wake of a wildfire…

And yet, people who have lost their homes in a climate disaster often get insurance payouts for less than the total replacement costs to rebuild their homes to even current building codes, let alone the more expensive resilient standards. Today, if homeowners want to rebuild their home to the IBHS standard, they have to come out of pocket, underscoring the need for flexible and dedicated financing products that can make it easier for homeowners to make critical resilience investments.

Building to more resilient standards is possible, but it requires answers to questions like, “Who is going to pay for it?” and “How will they afford it?”

While government, insurers, and mortgage holders all benefit from a resilient housing stock, homeowners ultimately bear the long-term risk of losing their home or it becoming uninsurable.

Investing in home resilience is an investment in the homeowner’s future—avoiding losses, policy cancellations, and rising insurance costs as climate risks increase.

The good news is that there’s plenty of precedent for designing financial products for homeowners. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) offers a blueprint for what’s possible. Founded in 1934, it was created to make homeownership more affordable at a time when only one in ten Americans owned a home. The FHA reduced down payment requirements, extended loan terms up to 30 years (most loans in the 1920s and 1930s spanned 3-5 years), and introduced the concept of FHA loans for first-time homebuyers.

We need that same innovative spirit today—but focused on financial products that make climate-resilient retrofits and rebuilds affordable for every homeowner. It’s time for the next renaissance in financial products for homeowners.

Have thoughts to share on this piece, or want to add your voice to the conversation? Reach out!