The Weekly: Takeaways from 2025’s Climate Disasters

Twenty-three billion-dollar disasters, $115 billion in damage, and not one hurricane: 2025 was a masterclass in how climate risk in the U.S. has changed.

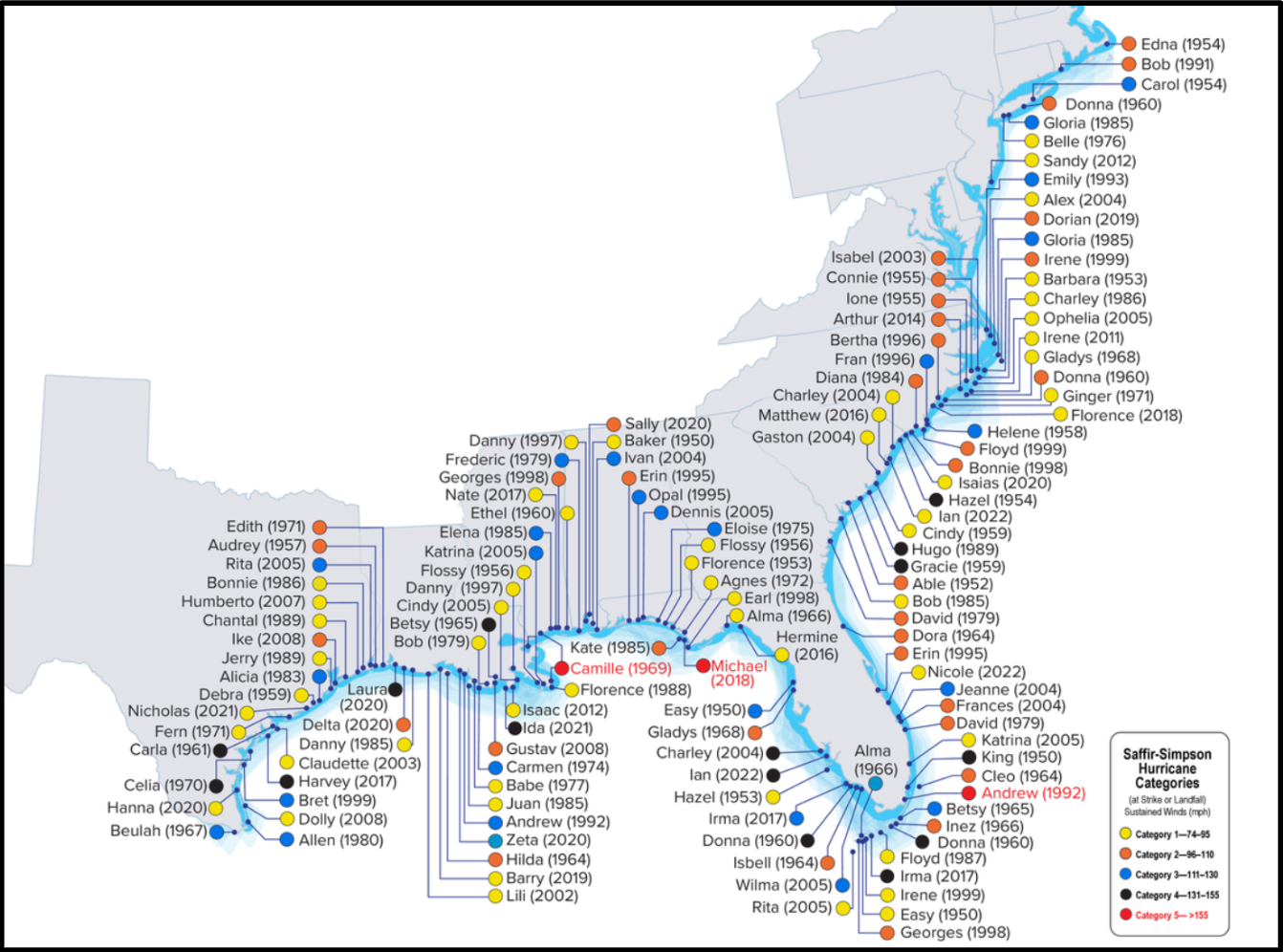

Hurricanes are the most costly type of climate disaster. The high cost comes from population growth in hurricane-prone areas, incentives that motivate rebuilding in those same areas, and physical assets in harm's way that aren't designed to withstand severe hurricanes.

The 2024 hurricane season led to over $100 billion in economic losses and more than 320 deaths, with 17 named storms, including five major hurricanes. Before we break down the cost drivers making hurricanes so expensive, it’s helpful to understand the magnitude of their impact:

Unlike wildfires or hail storms, the damages from hurricanes are multidimensional and stem from:

Of the 16 most expensive hurricanes (cost adjusted for inflation) in U.S. history, 15 have taken place since 2000 (the one outlier was Hurricane Andrew in 1992). What’s making recent hurricanes so costly? Here are four main drivers:

More Americans today live in the paths of hurricanes. Americans are flocking to coastal areas; between 1970 to 2020, the population in coastal counties increased by 40 million people, or approximately 46%. For example, two coastal metropolitan areas–Houston, Texas and Tampa Bay, Florida–have grown significantly since 1980, with greater Houston adding 1.3 million homes. Even with updated construction to make buildings more resilient (as we’ll discuss in Driver #3), the savings from more resilient building codes and materials still can’t keep up with the increased costs from greater asset exposure. Swiss Re, a major global reinsurance company, suggests that all the hard-won gains from stricter building codes have been undermined by the explosion of growth along the coast.

As the population of coastal communities has grown, so has the value of physical assets in harm's way. Shoreline counties hold 50 million housing units, and $1.4 trillion of assets sit within an eighth of a mile of the coast. In Florida alone, home prices have increased 80% in just the last five years. Between 2013 and 2023, home prices in Florida grew 164%, making the state the second highest in single family home appreciation in the country.

Home prices in cities hit by hurricanes increased further after a hurricane hit. A 2021 study that compared home price appreciation in the year before and year after major hurricanes, found that in the year before Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans, home prices were appreciating at 97% of the nationwide average. In the year after the storm, they increased to 109% of the nationwide average, on account of reduced supply but sustained demand. Similar results were observed from other major hurricanes across the southeast.

Research from 2023 corroborates this finding, but adds an important nuance: in the immediate period after a hurricane, incoming homeowners have higher incomes, leading to an overall shift toward wealthier groups and an evolution in the demographics (and inequality) of regions hit by hurricanes.

Rising housing prices push people to buy in flood zones. In the wake of Hurricane Sandy in New York, Joseph Tirone Jr., a broker with the real estate firm Compass, spoke to the relationship between the lack of affordable housing and asset risk: “The demand is insatiable. There’s really not much else people can buy, so they buy in flood zones.” This particularly impacts lower-income buyers, including immigrant families and many BIPOC households. Hurricanes also generally lead to less affordable rental housing while rent prices increase by 4-6% in the wake of a disaster.

Federal programs actually incentivize people to stay in high-hazard zones and not relocate. In the wake of a disaster, it’s common to hear, “We will rebuild.” The refrain speaks to America’s resiliency as a nation and the willingness of people who have lost everything to start again. The federal government provides a range of financial assistance following a disaster, including FEMA and the Small Business Administration’s Disaster Loan Program and a variety of pre- and post-disaster grants. Through its National Flood Insurance Program, FEMA also provides federally-subsidized flood insurance to supplement the home insurance of people living in flood-prone areas.

Rebuilding is federally backed through subsidies, incentives, and insurance. While the impulse to rebuild in the wake of a disaster has been financed by the U.S. federal government, how that rebuilding works—including decisions about land use and infrastructure—is largely the purview of local officials, who often have an interest in replicating the status quo.

Older homes are more susceptible to hurricane damage. Due to less resilient construction materials and building codes, older homes are more susceptible to heavier hurricane damage. For example, the average life span of a roof in Florida is 12-20 years, leaving homes built before 2002 more likely to break down from heat, moisture, and wind exposure. 69% of the homes in the path of Hurricane Ian were constructed before 2000, meaning their construction was more vulnerable to wind speeds over 100 miles per hour (Hurricane Ian made landfall with 150 mph wind speed).

It’s worth noting that Florida’s current building codes, implemented in 2002, are considered to be some of the toughest in the country, and have resulted in reduced losses from hurricanes. The strengthened code requires more hurricane-resilient materials, construction and flood protection.

From 1979 to 2017, the number of major hurricanes has increased while the number of smaller hurricanes has decreased. Changes in climate are directly contributing to this increasing hurricane frequency and severity:

Between the increased frequency and severity of hurricanes and population growth into hurricane paths, there’s no question why hurricanes are so expensive. Add to that an aging housing stock and disincentives to relocate, and it might seem like hurricanes will continue to be as costly as they have been in recent years.

But as we explore in Part II of this Hurricanes briefing, there are specific opportunities to reduce that cost, reduce risk exposure, and fortify existing buildings and infrastructure in ways that mean less destruction and less cost.

Have thoughts to share on this piece, or want to add your voice to the conversation? Reach out!